The Basics

The circle of fifths is a handy

tool for organizing the 12 possible Major scales into what is called KEY SIGNATURE.

In the Major Scale Lesson, we

learned that "key" refers to the starting note (root) of the scale. "Key

signature" simply refers to the number of sharps or flats that occur in each key. No

two major scales will contain the same number of sharps or flats, so scales can be easily

organized by key signature.

Let's take a look.

As we learned in the Major Scale

Lesson, the C Major scale contains no sharp or flat notes - C D E F G A B. This is the

only Major scale with only natural notes. All other keys will have a varying number of

sharp or flat notes. Each key has a unique key signature.

If we build our next scale

starting with the 5th note of the C major scale, we get the G Major scale - G A B C D E

F#. Notice that the G Major scale has one note that is sharp (F#).

Now, lets build a third scale

starting from the 5th note of the G Major scale. That will give us the D major scale - D E

F# G A B C#. Notice that we now have two notes that are sharp (F# and C#).

If we build a fourth scale from

the 5th note of the D Major scale, we get the A Major scale - A B C# D E F# G#. As you've

probably guessed, the A Major scale has one more sharp than the D Major scale.

That's how it works.

If you build a Major scale from

the 5th note of another Major scale, the new scale will have one more sharp than the scale

you started with.

That's where the "5ths"

in the circle of 5ths comes from, but what about the "circle" part? The circle

comes from the fact that if you continue to build a scale from the 5th note of the

previous scale, you will eventually wind up right back at the beginning, C Major:

G is the 5th note of C Major.

D is the 5th note of G Major.

A is the 5th note of D Major.

E is the 5th note of A Major.

B is the 5th note of E Major.

F# is the 5th note of B Major.

C# is the 5th note of F# Major.

G# is the 5th note of C# Major.

D# is the 5th note of G# Major.

A# is the 5th note of D# Major.

F is the 5th note of A# Major.

C is the 5th note of F Major.

We're right back where we

started, as if we traveled in a circle.

Now, one of the conventions of

key signatures is that a proper key signature does not mix sharps and flats. You have one

or the other, not both. Another convention is that the letter name for each note can only

be used once. These two conventions present us with a problem.

Once you get to a certain point

within the circle, it becomes impossible to observe these two conventions without

considering the note F to be E# and the note C to be B# or resorting to the awkward

designation of DOUBLE SHARP. (Denoted by x, a double sharp note is equivalent to the note

one whole-step higher than the letter name being used. Cx is the same pitch as D.)

Let's look at the key of F#:

F# G# A# B C# D#

E#(F)

In order to avoid using both F

and F# in the key signature, we have to "bend" the rules and name F as E#.

The convention of not using the

same letter name twice is a hold-over from written music notation. Each letter name is

given a line or a space on the staff. It would be very awkward trying to write both F and

F# into the same key signature.

Now, once you get to the key G#

in the circle of fifths, the dreaded double sharp appears:

G# A# B#(C) C# D#

E#(F) Fx(G)

At this point, things are getting

out of hand. So, what would happen if, instead of trying to use a G# scale, we were to use

Ab instead? (Remember that G# and Ab are the same note.)

Let's try it:

Ab Bb C Db Eb F G

Hey, that's a lot better than

that G# monstrosity!

So, let's take a look at key

signatures with flats instead of sharps.

If we go back to the C Major

scale (C D E F G A B), but instead of going to the 5th note, we go to the 4th note to

construct our next scale, we get the F Major scale- F G A Bb C D E. Notice that the key of

F Major has one flat.

If we build our next scale from

the 4th note of the F Major scale, we get the Bb major - Bb C D Eb F G A. Notice that we

now have two flats.

It's the same pattern all over

again.

If you build a Major scale from

the 4th note of another Major scale, the new scale will have one more flat than the scale

you started with.

And once again, if you keep

going, you're going to end up right back at C:

C F Bb Eb Ab Db Gb

B E A D G C

Let's reverse the order of those

notes:

C G D A E B

Gb(F#).....

Hey! Wait a minute! Isn't that

the same order we had before, when we were working the sharps? (Go back and take a look.)

It sure is.

If we take our original circle of

5ths and change each sharp to its flat equivalent we get this:

C G D A E B F#/Gb

Db Ab Eb Bb F C

Now, since we're calling this a

circle, let's look at it that way:

| C |

0# |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| G |

1# |

F# |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| D |

2# |

F# |

C# |

|

|

|

|

|

| A |

3# |

F# |

C# |

G# |

|

|

|

|

| E |

4# |

F# |

C# |

G# |

D# |

|

|

|

| B |

5# |

F# |

C# |

G# |

D# |

A# |

|

|

| F# |

6# |

F# |

C# |

G# |

D# |

A# |

E# |

|

| C# |

7# |

F# |

C# |

G# |

D# |

A# |

E# |

B# |

|

| C |

0b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F |

1b |

Bb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bb |

2b |

Bb |

Eb |

|

|

|

|

|

| Eb |

3b |

Bb |

Eb |

Ab |

|

|

|

|

| Ab |

4b |

Bb |

Eb |

Ab |

Db |

|

|

|

| Db |

5b |

Bb |

Eb |

Ab |

Db |

Gb |

|

|

| Gb |

6b |

Bb |

Eb |

Ab |

Db |

Gb |

Cb |

|

| Cb |

7b |

Bb |

Eb |

Ab |

Db |

Gb |

Cb |

Fb |

|

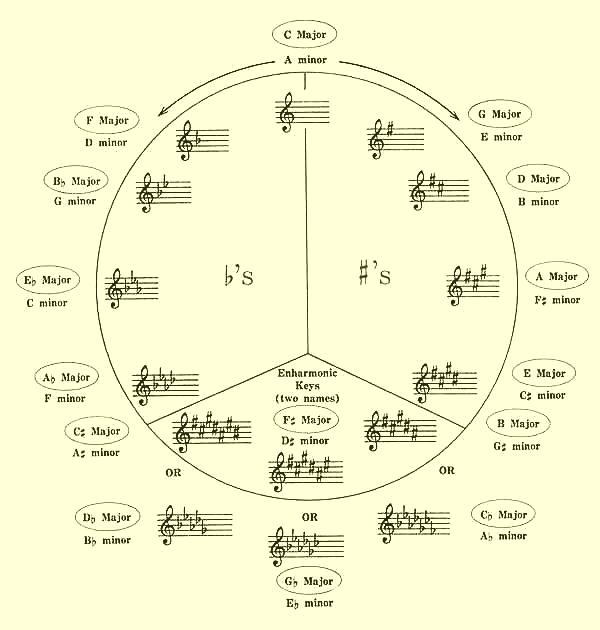

The Circle of Fifths - Major and

Relative Minor Keys

C is at the 12:00 position,

because the key of C has no sharps or flats.

If you travel clockwise around

the circle to the 6:00 position, each successive key has one more sharp than the preceding

key.

If you travel counterclockwise to

the 6:00 position, each successive key has one more flat than the preceding key. Moving

counterclockwise around the circle is sometimes referred to as the circle of 4ths and also

referred to as "back-cycling" through the circle of 5ths.

Now, let's take a look at F#/Gb:

F# G# A# B C# D#

E#(F)

Gb Ab Bb Cb(B) Db

Eb F

It makes no difference whether

you use sharps of flats with this key. Both give you the same result. If you use sharps,

you end up having to refer to F as E#. If you use flats, you end up having to refer to B

as Cb. It's pretty screwy, but there's nothing to be done about it.

Here's a handy sing-song for

remembering which notes are sharp or flat in each key:

Sharps = Father Charles Goes Down

And Ends Battle.

Flats = Battle Ends And Down Goes

Charles' Father.

Each successive key not only adds

a new sharp or flat, but keeps the sharps or flats that were present in the preceding key.

Moving around the circle

clockwise yields G (Father), D (Father Charles), A (Father Charles Goes) etc... The key of

G has one sharp, which is F. The key of D has two sharps, which are F and C. The key of A

has three sharps, which are F, C and G etc...

Moving around the circle

counterclockwise yields F (Battle), Bb (Battle Ends), Eb (Battle Ends And) etc... The key

of F has one flat, which is B. The key of Bb has two flats, which are B and E. The key of

Eb has three flats, which are B, E, and A etc...

The fingerboard

The circle of 5ths is very easy

to visualize on the fingerboard:

The circle of 4ths

is just as simple:

In each case, you start with C,

and add a sharp or flat for each successive key. It doesn't get much easier, folks.

The circle of fifths falls into

the category of "something handy to know but not something that you can really

practice"... that is, until you begin analyzing songs and/or writing your own songs.

Many common chord progressions follow the circle of 5ths. The more familiar you are with

this device, the easier you will be able to spot it's use within a song.

One use for the circle of 5ths in

a compositional sense is as a key changing device. Changing the key signature in the

middle of a piece of music is called MODULATION. The smoothest modulation occurs between

keys that have only one note difference between the two keys. If you've been paying

attention, you should realize that this is exactly how the keys are organized with the

circle of fifths.

A good way to practice

modulation, utilizing the "circle", is to pick a position on the guitar neck and

"run the scales" through the circle. Without moving up or down the fingerboard

more than one fret, you should be able to pick out each successive sharp or flat key and

play that Major scale.

If you are soloing over a chord

progression that suddenly shifts to a new key, the ability to quickly change to the

appropriate scale is a must. You won't always have the luxury of shifting your hand

position in order to change to a new scale.

Learn your scales.

Learn your fingerboard.

That's the only way

CALL

973-785-0896

tom@newjerseyguitarlessons.com